I have a very clear memory of riding a double-decker bus in London one Saturday night on my way to a club when I was about 20 and studying abroad there. I’d made two very good friends and one of them finally ventured into a topic I never willingly brought up: my love life. She said I was very tight-lipped about the subject and, sensing my reluctance to broach it, never asked me about it. This was, of course, her effort to now ask about it, emboldened by a few terrible vodka shots we’d had in our flat.

I immediately trotted out my default (but genuine) response that, while I’d never voluntarily offer up information about it, she was always welcome to ask me anything and I’d answer her honestly. And so, on our way to club 1 of 4 (I don’t know how I ever had the energy), we debriefed on all things love and Nora.

I meant what I said: anything she asked me about, I answered with complete sincerity. The issue, though, is that I’m not sure how willing I was. This was neither the first nor the last time I shared things about myself so ruthlessly. The feelings I felt in the aftermath of talking, were familiar, too: an uneasy notion that I can’t help but tell the truth. At least with her I’d shared safely.

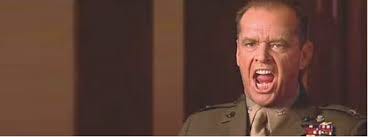

I once read a biography about Jack Nicholson in which the author cited the actor as saying that he couldn’t help be “compulsively honest.” This phrase really stuck with me. I’ve never been able to find the original quote and it doesn’t help that I also can’t remember the title of the book—all the covers of Jack Nicholson biographies feel like “the one” until I see the next and revise my previous declaration. It’s not my fault—I randomly pulled the book off a Los Angeles public library shelf six years ago.

But I don’t need more context to feel a deep resonance with Nicholson’s (alleged) feeling. The biographer said the actor expressed some bemusement at this tendency of his when he was on talk shows and couldn’t help but give honest answers to the show hosts. It’s funny that one of Nicholson’s most famous lines is “You can’t handle the truth!”

Nicholson’s words perfectly captured how I felt all those years ago on the bus, as well as before then, and since: that something deep inside me impels me to tell the truth regardless of whether it exposes me, benefits me, or hurts me. But I think this is wrong. And I need to stop.

I don’t know where this impulse comes from. Perhaps there’s a memory I’ve forgotten in childhood of telling someone the truth and not being believed and so, in a reverse “Boy who cried wolf,” I’ve spent the years since being overly earnest so that when my credibility is finally questioned, I’ll have an undeniable record of honesty.

Or maybe it comes from this bizarre metric I live my life by. Everything I do in life, I ask myself: “Would this hold up in court?” You can ask friends of mine who’ve heard me mutter this as I make decisions. For instance, I keep receipts for purchases that I feel weren’t totally smooth so that, in case I’m one day part of a lawsuit, I can say: “Your Honor, while I know the prosecution would have you believe I stole that T-shirt, I in fact have the receipt proving the exchange of a small white for a medium white.” At which point the jurors and the crowd (yes, my trial is always packed in my imagination) would gasp and I’d share a smug little smile with my counsel.

More relevant to the topic of dismal honesty is the idea that if I come fully clean, I’ll have an alibi. I do this a lot in work situations. My gasp-worthy twist would sound something like this: “Your Honor, would someone who voluntarily admitted to mistakes she made when processing the return of three corduroy pants, someone who went to great personal lengths to ensure the customer felt my sorrow for my mistake, someone who didn’t care how much shame was heaped upon her house and name so long as the return was then processed in favor of the customer, ever hide that she accidentally charged the wrong amount for an oxford shirt? Can this person who runs to confess her sins possibly be the same person who strives to hide them? I think not, Your Honor.”

With all the mental effort I’ve put into creating a case to exonerate myself over the years, I almost hope I’ll one day have a grand trial of this sort.

But back to important things: it’s possible I’ll never know why I’m “compulsively honest.” What I do know, is that I can’t keep doing it.

In a script I wrote some years ago, I lent a character a metaphor I’ve often used to express how this need to be fully transparent can make me feel: like a chocolate bar. It’s as if I live life with a sense of obligation to give parts of myself to others simply because they asked for it. I can’t imagine not giving something to the person who demands it.

It reminds me of being in high school and bringing a snack for recess. When girls would ask me for a cracker, how could I say no? So, I’d cave, knowing this would lead others to ask for some and soon, I’d be cracker-less. This is why I’d sometimes scarf them down really quickly, half-turned away like a naughty dog with stolen sausages. Or I’d sneakily eat a few out of sight and leave the rest in my bag. Or I’d simply not bring crackers so no one could ask me for some.

This probably all goes back to an inability to say “no.” It’s true, I struggle with it. Is it because asking for things is difficult for me, so I feel I must reward someone who musters up the courage to ask, ignoring that this might not be a hard thing for others? Possibly.

The problem with giving chunks of Nora The Chocolate Bar away is that at some point you’ll be left with nothing but a pretty wrapper. While this is dramatic writing (trust me, it works in the script), it does capture how this compulsion to tell the truth can feel, and what I imagine made Jack Nicholson dislike it, too.

It betrays a lack of self-respect. Giving myself away to anyone who asks with no discernment is not the action of someone who values what they are giving away. And that’s a huge issue. And while you may or may not value yourself, you’re left feeling pretty bad after sharing without a moment to consider your actions. You acted so swiftly that before you could even think about whether you wanted to share or not, you have. And even if that person was someone you wanted to open up to, it leaves you feeling robbed of the choice to do so.

It seems I’ve been a little loose with my personhood. That perhaps my inner world has not been treated like the temple it is. That perhaps I’d have benefitted from heeding the words of prudish mothers in booklets from the 1800s about how good girls behave and who sees their ankles (or in my case, my secrets).

A recent experience has alerted me to the danger I’m in, the self-extinction of my privacy if I’m not careful: the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, commonly known as Fringe.

Any young person who wants to get into acting and writing hears endless quotes about how you must give yourself to your art, you must let yourself speak from your heart, you must use yourself fully if you want to make great work. There’s something so romantic in this that most of us believe it and do so to harmful degrees. It’s an almost predatory notion that’s spread to young people. Tarantino, someone who is frequently held up to aspiring creatives as the person to emulate, even has a quote about this that I’ve seen splattered across countless Instagram accounts about film: “Make it personal enough so you feel embarrassed to share it.”

Doesn’t it sound a bit…self-exploitative? Like the film industry is Ursula asking young artists, i.e. the Little Mermaid for her voice in exchange for feet? I think so. And I’ve fallen prey to this.

I wrote a one-woman show that drew significantly from things I’ve experienced all my life. The plot itself was largely made up, with some important exceptions, but the feelings were all intensely real. And for 21 days I shared these emotional secrets to anyone who would come through. I practically begged people in the street to see the show. And they did.

At first, I imagined success would be inevitable. After all, everyone has been telling me for years that if you are brave enough to share the truth, to say the things others don’t dare say (which is the artist’s duty), people will respond. They will recognize you are speaking deeply human things that will inevitably resonate with them and create ripples in society. I felt I did that—I spoke truths that go to the core of who I am and that I know have meaning for others because spectators (friends and strangers) came up after the show to tell me I’d done that for them. Incredible.

So why wasn’t I successful professionally? Many reasons. Reasons that matter more than telling the truth. Maybe if I’d had more resources and more visibility I’d have been a hit. If more people got to hear it, they might have pushed me to fame. While I’ll never know, I’m not fully sold on this.

Instead, when the run ended, I felt gutted. Not only had I shared my secrets over and over for days, which took its toll, I’d done it for nothing. I’d given myself away, and no one cared.

A very toxic thought popped into my head: had I not given enough?

I tried to come up with even more gut-wrenching truths I could confess to in play-format. Things I could find the courage to speak if that’s what I needed to do. Perhaps I hadn’t been as brave as I’d thought. Perhaps, the artistic devil whispered in my ear, I was still protecting myself and withholding some truths.

But something inside of me must have known these evil words were just that. I reminded myself: how many utterly ridiculous shows that give nothing away of the creator are brilliant and successful? Many. I knew being honest couldn’t be the only thing standing between me and success.

It was a struggle to push back these thoughts. Today’s society values increasingly invasive looks into people’s lives. It’s an arms race, but to personal details. Whoever can reveal the most goes viral. Unabashed “Day in my life” of people who eat too much (per their own words) and want to show that, of people who work in adult film, of people who are experiencing grief. There is nothing wrong with the content any of these videos, of course: they’re simply depicting things people have historically wanted to keep private. Nowadays, if you are willing to share what most people still consider private, you’ve won.

I’ve written a script about this need to reveal more than anyone else (not the same one with the chocolate bar lines). It’s focused on the particularly noxious intersection of art and revelation. How artists are expected to reveal more than others, to give themselves over fully to their art for viewer’s sakes. And, sadly, how many of us do so willingly without thought to the consequences.

I believe you can make great art without having to show as much of yourself. It’s a lesson I’ve learned: that you can be in it without showing how. I wonder if this was always the point and I just misunderstood or thought that if I made the line between art and self thinner, it would be better, more impressive. How ambitious and useless. If I’d just looked at Van Gogh’s The Starry Night, I could’ve known. Can anyone doubt his heart is in it even if he’s not in a more obvious way? I bet that if I’d painted it, I would’ve added a person I cared deeply about or set it somewhere that means a lot to me. Am I just a heavy-handed, young artist who with time will learn the beauty and strictures of mastery? I hope so.

Either way, what I need to work towards is telling the truth, without it being my truth.

This is why I think it’s time I put an end to or at least curb this uncontrollable need to be honest. I’ve been a bit too careless with it, been hurt by it, and now learned from it. While I can’t undo the past, I can try to be better in the future. Treat myself less like a chocolate bar I have to share at recess and instead give meaning and value to the select few I choose to share chunks of myself with.

I’m aware of the irony of me literally announcing this to the public in an article no one asked for that discloses these personal feelings. But as they say, old habits die hard.

I’ll end with this thought—it’s a pity, I’m Jewish. With my great desire to confess, I could’ve been an excellent Catholic.

"With my great desire to confess, I could’ve been an excellent Catholic." :'D

I love this, and I understand it to a certain extent. Honestly, I thought this was going to explore how people don't really want the truth from others, or they only want it if it’s wrapped up nicely, like a piece of chocolate, to use your metaphor. But I like the different angle. You're probably a nice person.

For me, being compulsively honest has more to do with people not being ready for it. Yes, musicians, writers, and artists can get away with it, but they sure pay the price. As someone who struggles to craft a persona and is slightly rude, with a face that speaks a thousand words, I’m trying to figure out how to be politely dishonest, but I’m starting to wonder if it’s worth it.